Telling Others I'm Autistic (Disclosure)

(This is a recording of this blog post)

Did you read the short blurb for this post? If not, here it is again:

You've realised later in life that you're autistic, and you'd like to tell others... or do you? How would you even go about doing that? And why does the word 'disclosure' feel so heavy? And what if the people you tell end up having a disappointing reaction?

These are some of the most common questions and concerns that come up in my sessions when autistic people are considering sharing with others that they're autistic.

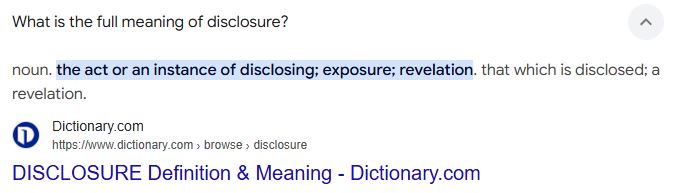

I don't know if this is an autistic thing or because English is my second language (or because English is my second language and I'm autistic) but I always check the definition of whatever concept I'm about to explore - in this case, Disclosure.

Expose, reveal, confess, divulge... Pretty heavy words, in my opinion. And, to add insult to injury, the opposite of disclosure is 'concealment'.

Others have compared it to 'coming out of the closet' - either, appreciating what it must be like for some LGBTQIA+ people, or, often, the person I'm talking to has already 'come out of the closet' once and feels the weight of doing it again, this time as autistic.

There's absolutely nothing wrong with using the word 'disclosure' in this context, but I rarely do. Simply because I think the word has such heavy connotations (like 'confession' or 'expose' or, as mentioned, 'coming out of the closet' - which is also a bonkers expression indicating you're the 'odd one' that has to declare that you're different, urgh!), and when already nervous about sharing our autism realisation with others, I don't think it's necessarily helpful to use a vocabulary that adds to this nervousness.

But it's also relevant to look at the term disclosure because when I ask people why they want to share their autism realisation, a very common comment is that they feel they're hiding something, that they're being secretive, withholding information, or concealing something, which makes them feel dishonest and not transparent. Most autistic people I know value transparency and honesty very highly.

That doesn't automatically mean it's a good idea to share that you're autistic. So, before listening to your values system, consider these things first:

Why I want to share, I'm autistic

1) Why do you want to share that you're autistic?

- Transparency

- I'm so proud and happy to have found out I'm autistic, and I want to buy the t-shirt and yell it from the rooftops

- I thought I had to, to be a 'good' autistic person and help change the narrative of what autism is and looks like

- I need accommodations ('equitable requirements'*) to be made

- I want to feel accepted and understood

- I need people not to judge me when I do this [insert behaviour you want understood]

- It will make it easier for people to understand me and make space for my needs

- My closest have a right to know

(Is your reason here or do you have another one you'd like to share and for me to add?)

2) What do you hope to achieve by sharing?

- Acceptance

- Understanding

- Help/support

- Leeway/grace/patience

- Interest

- Nothing

(Again, are your hopes listed above, or do you want to share one I haven't?)

Gaining clarity around why we're sharing or want to share will make it easier for us to gauge whether our 'why' is realistic and to guide the conversation in the direction we want, to achieve our desired outcome (without any guarantees, of course).

Other people's reactions

A major obstacle to telling others is that we don't know how they'll react. And once it's said, we can't unsay it. We can rehearse and plan the conversation a hundred times over, but there's a good chance it won't go as planned because we're dealing with an 'unknown' factor - the other person's reaction. And depending on that reaction, we might discover this is a really safe person (someone who makes us feel accepted, seen, heard and understood without judgement and with a gentle and kind curiosity) and our plan doesn't matter because we're having a yummy exchange. Or, we might find that we're not with a safe person and are met with stereotypical comments that rile us up or shut us down.

Personally, I wasn't expecting the hurt from what appeared on the surface to be a positive comment like: "That doesn't change anything. You're still you." Because I wasn't. They knew a masked version, and/or they didn't know me very well at all, and I wanted to know if they were safe to unmask around and if they'd still accept all of me.

I'm going to write a blog post called "A Short Guide on How Not To Be a D*ck When Someone Tells You That They're Autistic"... Ok, I might change it to a more gentle title like 'How To Be a Safe Person..." that autistic people can share with allistic people. But common - stupid - comments from sharing you're autistic might be:

- You don't look autistic

- Are you sure? Where did you get your knowledge from?

- I don't think you are

- But you have a job/family, so you can't be?

- But you're maintaining eye contact, so surely you're not?

- We're all a little bit autistic

- Everyone has a diagnosis now! (eye roll)

- My nephew is autistic, and you're nothing like him, so I don't think you are

- Oh, but you're one of those high-functioning ones, then? What level of autism do you have? It can't be very severe.

Considering how absolutely (and I'm sorry for my language but..) moronic such comments are, it's staggering how common they are.

I'll address each of those in the before-mentioned blog post about what not to say (and feel free to contact me with other ignorant replies you've had if you want me to include them), but for this post, I'll stick to your reaction rather than theirs.

Such comments are exhausting for multiple reasons. Not only are they disappointing, but they're hurtful. Instead of being met with understanding or curiosity, we're met with energy-draining ignorance, which can detract from our limited spoons**. These comments might also trigger our internalised ableism (there's another blog coming about this topic).

Our reaction is a good gauge of what's going on for us. If we feel angry and defensive, it might be because we feel like imposters, and their words and our emotional or physical reactions are signs that we still have more work to do regarding self-acceptance. It might also be justified anger towards feeling constantly invalidated, marginalised, discriminated against, dismissed and/or rejected. If the feeling is more akin to hurt or disappointment, it might indicate that we'd trusted the person we told and presumed they were a safe person, and we've just realised they're not the person we saw them as or hoped they were. It might be an indicator that we have a tough and unwanted decision ahead of us as to whether this person stays in our lives, which is never a nice place to be (especially complicated if it's a family member who says this or someone we're sharing a home with). Or, your emotional and physical reaction might be something else - all I'm trying to say is that you can, if you want to, use your reaction as feedback for further personal exploration, reflection and self-development. The better we understand ourselves, the easier (not easy, but just easier) it becomes to self-advocate because we know ourselves better and can manage or control our emotions better (emotional regulation - something I'll cover in my psychoeducational programme).

These sorts of unhelpful comments are also energy-consuming because now we might feel the need to 'educate' the person we're talking to, and we don't have the energy or, perhaps, the words to do so. Maybe we're already tired; perhaps their comment shut down our ability to think clearly and speak. Or maybe we're still so new on this journey that we haven't developed a language around it all yet and are still learning, so how are we supposed to teach others?

It reminds me of 2020 and the time just after George Floyd's murder when the Black Lives Matter movement gained a lot of attention. As an anti-racist wanting to learn and know more, especially about my internalised racism, I was keen to learn from those in the midst of it. But I kept seeing posts saying "it's not my job to educate you" and my frail, white ego felt confused. If not them, who? How was I supposed to learn? The answer was - obviously - to not put additional pressure on the racially targeted group, working on saving lives, including their own, and fighting for justice, but for my white ass to do the work myself - by reading, listening and doing my own research. It's not like there's a lack of information out there about racism and how to be an ally.

It's not your job to educate others! But you can sign-post them to places where they can learn more.

However, I did have an aha moment a few years back during one of my post-identification support sessions.

I was listening to someone talk about the hardship of telling others and their fears of unhelpful reactions (a conversation I'd had so many times at this point where I usually focused on validating their worries and acknowledging how rubbish it is that this is yet another challenge autistic people face). But a little while later, we talked about autism as our passion topic - something we love researching and talking about with others - and that's when it clicked!

Many of us find talking about autism energising but educating others exhausting. But what's the difference? Partly, it's how the other person is reacting, for sure, but it's also partly what energy we bring to the conversation.

If we feel defensive, hurt, angry or another difficult or uncomfortable feeling when someone says something unhelpful about autism, our energy is going to be heavy and draining for us.

But what if, when someone says something unhelpful, we light up? They've just shown us that they lack lots of knowledge, and guess who has lots of knowledge and is eager to share? Us!!

So, when people say unhelpful, shaming, discriminatory or stereotypical stuff, I do a quick analysis of this person and whether I want to spend time and energy on them, in general (for instance, I went on a date with a professor in psychology (!), and we got on to the topic of autism, and he said all sorts of outdated nonsense, and I realised I'd never see him again and I wasn't in the mood to give him any of my energy so I just left it. It might have been a great opportunity to educate someone important, but I also have a right to protect my energy instead of actively participating in activism). If the person is worth my time and energy, I light up and say with positive, eager, info-dumping energy: "I love that you just said that, as it's such a common misunderstanding. Let me tell you about autism!"

The Recipe

Last year (winter 2023), our neighbour told me and my partner that his wife had terminal cancer (just quickly, it turns out the doctor was wrong, and she's receiving life-saving treatment and is doing ok!). For me, as a therapist, it wasn't too hard to respond, but my partner went into panic mode: What do I say? Am I supposed to ignore them? Am I supposed to offer them something? But what? How am I supposed to react now? ???

Our neighbour explained that he was sharing this news because he didn't want people to feel offended if he and his wife weren't as cheery as usual or didn't say hi. Changes were happening, and we were free to ask questions and they'd still love visitors whenever possible. This took the pressure off my partner regarding how to react because our neighbour explained his motivations for sharing this information.

And it made me ponder how many neurotypicals have that sense of panic when someone tells them that they're autistic, especially since the autism PR team isn't as great as the ADHD PR team (this is a joke! But I find in our society that ADHD has less stigma attached, and there's a bigger focus on the strengths or the 'cute, quirky' sides of being an ADHDer - actually, to the detriment of ADHDers and their struggles - compared to autism).

Anyway, back to my point - what if all the unhelpful or stereotypical comments are based on panic mode? Why not help those poor neurotypical people out?

So, I came up with this recipe of telling people we're autistic.

With this recipe, we're not only giving ourselves prep/planning time around sharing that we're autistic. We're also creating clarity for ourselves about telling others, and we're gently steering the person we're talking to as close to our pre-rehearsed script as possible to try and maintain as much control as possible during this conversation.

"I want to share something with you..." (setting the scene that you're about to share something important and you'd like their attention).

"And the reason I'm sharing this is..." (this is back to my previous point of getting clarity for yourself as to why you're sharing this. If it's just so your friends will accept that you go outside occasionally when at the pub, do they need to know that's autism if you're not ready to tell them? Or can you simply say that the noise gets to you, so you need small breaks? We don't always need to 'play the autism card' (as people often refer to this info as) if we don't want to. You're allowed to ask for your needs to be met and your personality to be honoured simply because you are who you are without additional information. You're, likewise, always allowed to share you're autistic with anyone at any time - just do it from a place of consent from yourself rather than based on some sort of pressure or based on assumptions around your right - or lack of - to be you. The second thing that this does is take the pressure off the listener because they now know why you're sharing this information with them.)

[Share you're autistic and however way feels authentic to you - followed by...]

"And it'd be really great if you could do me this favour..." (People love doing favours for others! It makes us feel good about ourselves. As long as it's within our capabilities. If you asked me for €1 million, I'd feel quite awkward when rejecting you, but if you asked me to tell you about disclosing you're autistic, I'd be elated to be able to be and feel helpful!

On the other hand, people hate being told what to do - demands - so, for communication reasons, it's helpful not to say, "So I need you to stop doing x as it's driving me nuts!" as it might get people's backs up and make them feel defensive.

Secondly, by asking them for a favour, you're helping the other person know how to react, and depending on who you're sharing this with and what you're hoping to achieve, you can steer the conversation in the direction you want. So you might say, "So, it'd be really great if you could do me this favour of reading this website/book or listen to this podcast to learn more as I don't have the energy right now to explain any further." Or, "[this favour] of being mindful of what you say next as there are many stereotypes out there, and I'm quite sensitive towards those". Or "[this favour] of asking me lots of questions as I'd love to tell you more".

This way, you're also encouraged to do some pre-sharing reflections around what you're hoping to achieve and put that into words which can be massively helpful for you too, not just the receiver.)

A loving and gentle reminder: Even if we say and do all the right things, communicate perfectly, plan and prepare to the nth degree, there are no guarantees about how someone else chooses to react, and we might get hurt anyway (just like we might end up being pleasantly surprised). But not everyone will be able to meet you where you're at, understand what you're going through or what you need and not everyone will be able to fulfil your needs.

So, when you're thinking about why you want to share you're autistic, consider if the person you want to share this with is able to understand, especially considering that they haven't spent the last 2, 6, 12, 24(...) months deep diving into autism and might never want to make it their passion project. If we're sharing this information in the hopes someone else will instantly 'get us' and make room for our needs, just be honest with yourself first - is this realistic, or does something else need to happen first?

I hope you found this helpful.

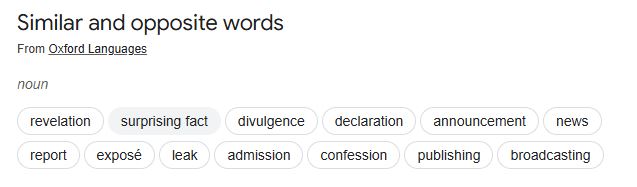

* Equitable requirements

I know a clinical psychologist from The Adult Autism Practice who doesn't use the word 'work accommodations' but 'equitable requirements'.

Accommodations can make it sound as if someone is going out of their way to make room for your non-standard needs. Equitable requirements state that everyone has a right to equity.

Here's a quick explanation of why equity is much more important than equality.

Imagine from: https://unitedwaynca.org/blog/equity-vs-equality/

** Spoon theory

Google it and you'll get an endless amount of results. This is a video by an autistic advocate Paul Micallef explaining it in the autism context: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KIW5rZZqVYo

Others prefer the 'fork theory': http://jenrose.com/fork-theory/

Others the 'ticket theory': https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o-bXAUUDCks

I tend to just talk about 'energy' - how much energy we have in a day, what takes away energy and what replenishes it (there's a free tool for that under resources), and sometimes, when I'm feeling cheeky, I might talk about 'how many fucks you have left' (swearing isn't for everyone. I'm raised in a country where swearing isn't a big deal, and it's also a verbal stim for me. I want to be considerate of those who find swearing offensive, but I'm also a bit confused by a specific row of letters and be offensive like 'fuck' when 'fudge' isn't, despite meaning the same...)

P.s. Because I'm dyslexic, you're bound to find spelling and grammar mistakes in my writing. I've always felt self-conscious and embarrassed about this, so I've done my utmost to remove them, asking for help or spending money I don't have on getting others to proofread my writing.

It wasn't until recently (late 2024), when I was writing a chapter on unmasking autism that I realised that my shame over my writing mistakes and hiding them or apologising for them was akin to masking. So, if you spot mistakes, I hope you can be a generous reader, and I hope you'll smile because you've just allowed me to unmask my autism in your company - thank you!